Memory Pieces

Experiencing Catherine Wagner’s Blue Reverie project at 500 Capp is a memory trigger. Not only because David Ireland’s house is a place that is so full of history and memories burnished into the surface of the shimmering walls. Inside there are the cracks of use and the patina of age within a transparent seal, these surfaces now serve as a backdrop, a stage for new activity.

For me, the memory trigger is of my past work with artists. People connect, orbit, and intersect over time. This is a narrative looped in place, in San Francisco art history, and it spans centuries. That sounds so epic in scope, but in fact, it is the truth—going from the 20th to the 21st centuries over the course of 25 years. Art history has a way of layering—500 Capp Street was built in the 19th century so there is a third one. Here we are, in 2025 considering two artists in convergence, in an aesthetic conversation.

In 1998, I worked with David Ireland and Catherine Wagner as part of a group exhibition, titled Museum Pieces: Bay Area Artists Consider the DeYoung at that museum in Golden Gate Park. Ireland and Wagner are two very different artists and personalities, yet both of their work grapples with history, makes visual sense, or in the case of Ireland, a bit of productive nonsense, of what came before. Both are also deeply connected to the Bay Area, as I have been. I feel a connection with this reconnection.

The DeYoung project came out of a wonderful and unexpected invitation. It was a validating moment when Steve Nash, who was then the Associate Director and Chief Curator at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, offered me the opportunity to organize an exhibition at the deYoung. (How times have changed—this was an invitation, not something I had to lobby hard for—he knew of my writing and curatorial projects in small SF galleries. Hard yes!) At that time, the museum, itself with roots in the 19th century, was housed in a stately but architecturally undignified building made homelier due to its seismic vulnerability. It was propped up with very visible steel beams at its front door, more like a walker with neon green tennis balls on its legs than a deconstructive architectural flourish. But the museum also was dowdy programmatically and its keepers knew it needed a refresh.

The charge was to find a way to connect a group of contemporary artists who lived and worked in the Bay Area to the DeYoung, to make itself more relevant. In conversation with Nash and then FAMSF Director Harry Parker, we settled on the premise of inviting artists to make new works responding to the crumbling museum.The deYoung was anticipating its future in a more glamorous 21st century building designed by Herzog and deMeuron. (It is worth noting that back then, the building design was highly controversial, viewed by many vocal locals as a modernist abomination .) I was truly honored to have been asked to do a project like this, one that grew out of my presence as an art writer—Nash was aware of my reviews and essays in the Bay Guardian-- and smaller curatorial projects that I'd done here and there. This would be my first exhibition that I organized for a museum.

I asked artists who were part of my community or had admired from a close proximity in writing about their work— Rebeca Bollinger, Chris Johanson, Deborah Oropallo, Maria Porges, Rigo 99 (23), Harrell Fletcher and Jon Rubin. who were at the time a team, as were Sergio de la Torre and Julio Morales. But it was also an opportunity to connect with artists who seemed legendary for their contributions-- Tom Marioni, for his Bay Area Conceptual chops, and Doug Hall, a media arts pioneer and SFAI faculty.

Nash and I discussed Ireland and Wagner for their interest in architecture and history: Ireland also had role in Bay Area conceptualism but also had a strong relationship to historic buildings— transforming the military buildings in the Marin Headlands into the art center, and of course 500 Capp Street, the house/artwork that is his greatest work.

Wagner’s iconic photographs of the Moscone Center under construction, and her visual interrogations of homes and classrooms in separate bodies of work, also seemed like a perfect fit for the show. This project was my first meeting with Wagner—who has been a colleague and friend ever since. From the start she was a dynamic force, full of ideas and enthusiasm. She immediately had an plan for how to engage with the museum—to look at its infrastructural elements and photograph them formally. She wasted no time setting up a studio on site to photograph display hardware as well as ledger books of the museum's initial collection. The latter, a fascinating history lesson in themselves, included an extremely eclectic range of materials, art and artifacts that seemed more like a flea market kunstkammer than a 21st century museum. The ledger books had lovely, marbled endpapers and notations in florid script, probably made with fountain pens. These served as her photographic subjects. We had great conversations, and it was thrilling to see the work emerge from out of the dusty warrens of the museum basement.

Working in situ, I have learned, is her forte.

It is particularly satisfying to work with artists on new projects because there is a sustained dialogue, relationships that build. I lived in the Mission at the time, and would pick Ireland up at his house to go to the museum for meetings and for installation. I’m not sure if he was carless or if he was an environmentalist who preferred carpooling, but the shared commute provided an opportunity to get to know him better. Those interactions provided the first times I had entered the magical place where he still lived. Before that time, seeing him around town at art openings and events, I was intimidated by his looming presence. He had a deceptively earnest demeanor, the San Francisco artist as tall and wise white-haired as John Baldessari was in LA, both had that clichéd, godlike vibe. Being able to enter Ireland’s world humanized him, to a point. To me, he was something like another David—Lynch, an all-American eccentric. Ireland told me about his daily habits, about how each morning he would sweep the sidewalk outside his home, a former accordion-maker's shop, and how amidst the leaves and soot would be used syringes and condoms from the neighborhood's night street life. The act was wholesome, but the setting was hardly that. He was a scrappy, mischievous artist.

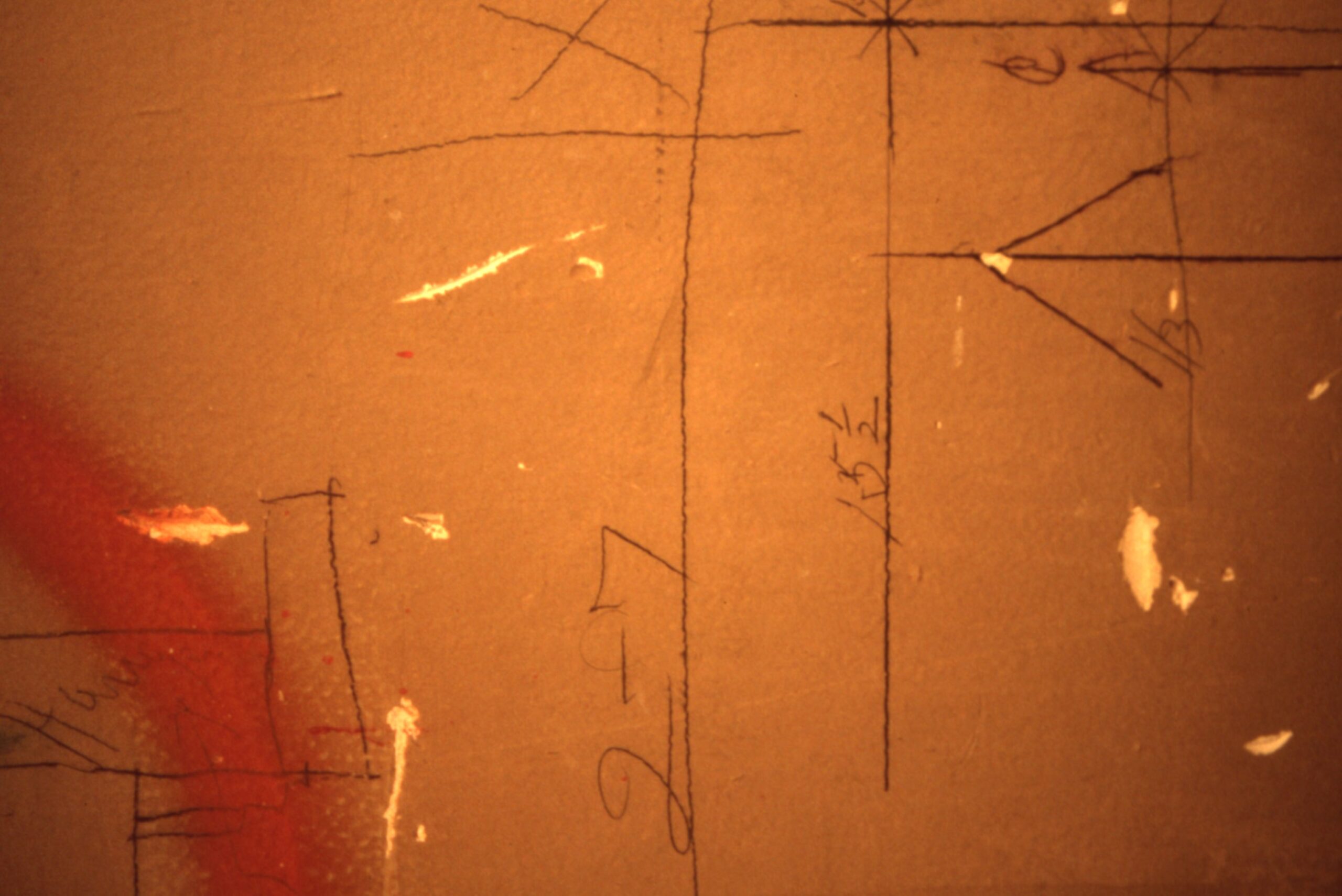

David also had a clear idea for a project at the de Young: to cut open one of the gallery walls and expose the infrastructure. I loved the gesture and was amazed that the museum went for it. He wanted to go even further, to poke all the way to the exterior, literally letting in fresh air. Therein was his prankster spirit, pushing things to the limit. The de Young team was wonderful to work with, and I think we benefited from the disrepair of the building-- to remove a sheetrock wall wasn't such a big deal in a structure that wasn't much longer for this world. (It felt like this was the last show, but the museum wasn't demolished until 2002 . This was another form of humanization, like performing surgery on an institution.

We didn’t know what we would find inside the cavity of that wall. Would there be dead animals—or even a body, as was later discovered at the Henry Kaiser Pavilion in Oakland when they were doing renovation work there? What was inside was a very different kind of surprise: The exposed wall was brick seemingly slathered with black tar, with white streaks of lime, with traditional red brick above—through this project we all learned that the building was a mishmash of additions and subtractions. Ireland laid that bare, as did Maria Porges in an irreverent audio tour. But the real surprise was the pale brown concrete pillar with two letters in red spray paint. I,D,I. From one angle it read ID—Freudian or identification-- and from the other, DI, the artist’s initials. Ireland fumed at the coincidence. It was too perfect, almost cutesy in its cosmic whimsy. He had a real, unwitting connection to the building. He called the piece Disclosure.

I suppose there is also a coincidence to the repeated connection between Wagner and Ireland in 500 Capp. In Museum Pieces, the two artists were in the same gallery, along with three portraits—of chief curator, director, and guest curator (me)—white men-- painted by Caitlin Mitchell Dayton. Looking back at the images, I still think there was a pretty good dialogue in that room.

Writing this was an opportunity to dig into my archives. I found Wagner’s wall label, which featured a quote. She wrote of her pictures:A quarter-century later, that latter term resonates with Wagner’s recent installation. Enigmatic objects abound in 500 Capp, a house which itself is a support system. Ireland’s ultramarine blobs, Wagner’s wooden fragments and the large photographs of blue light bulbs– these touchstones that encapsulate ideas and inspirations for another chain reaction yet to come.