Lesdi Goussen Robleto in Conversation with Tony Labat: Reflecting on the 1980s and the Legacy of Artspace

This interview is adapted from a longer conversation that took place over the span of an hour.

L: To commemorate 500 Capp Street’s Annual Auction, I want to take the opportunity to center your work as a critical interlocutor in the Bay Area conceptual art movement, alongside the legacy of Anne MacDonald. I’m interested to learn about how your participation with Artspace speaks to the broader impact that Artspace had in supporting local artists, since its inception in the 1980s.

In a previous interview with our Interim Executive Director, Jennifer Rissler, you were asked about the role that artist-run spaces had on your trajectory. You mention the influence that Langton had on your work during your time as a student. Can you elaborate on this question? What other spaces proved to be formative for your practice during the 1970s?

T: Langton– which was on Langton Street– which later moved to Folsom and became New Langton Arts was established by Jim Pomeroy and Jock Reynolds. Another [space] was La Mamelle, they concentrated a little bit more on media and performance, where Langton was open– music, sound, installation, performance and all sorts of things. In those days, [there was also] Howard Fried and the Performance Video Department– which later became the New Genres Department.

There was also a strong connection in the West Coast– in LA, you had [LACE]…and San Diego, which had some interesting spaces. You [also] had the Kitchen in New York [and] Hall Walls in Buffalo, in Upstate New York– they were just really amazing. It was an interesting network where if you got your foot into one of them, you basically would apply to the other ones and be able to tour, going from city to city to all of these alternative spaces.

It was [a] really beautiful network to support artists that were not making commercial gallery work. They were doing more like video and performance and installation, which is what I immediately got into when I arrived at the Art Institute and [began] studying with Howard Fried and Paul Kos, and David Ross [I got there in 76].

L: How did your time at SFAI facilitate your engagement with these spaces?

T: There was no manual for how to teach performance or installation. It was an open space– an open place to experiment, to find your voice, your vocabulary, your language. It was an opportunity to not think of yourself as a student and be limited by that, but to think of yourself as an emerging artist. And Howard and Paul created that atmosphere from the get-go.

I was [also] blessed with being an intern at the Museum of Conceptual Art with Tom Marioni at the same time, [and] ironically, I was an intern [of] David Ireland [in 78]. I was there, as you probably know, documenting the whole process [maintenance activity].

So my education, my foundation, was really that triangle– not really having much to do with the SFAI. It was kind of like we were on the other side, away from the building in the parking lot, Studio 9 and 10. Karen Finley was a student with me. Bruce Pollock. Katherine Sherwood. Anyways, we saw ourselves as emerging artists, like I said.

[In that time] Langton had a process. You proposed a work, a piece, an idea that you

would execute. Putting this in context, it wasn’t like, “oh, I’m a student, I’m not at that 1

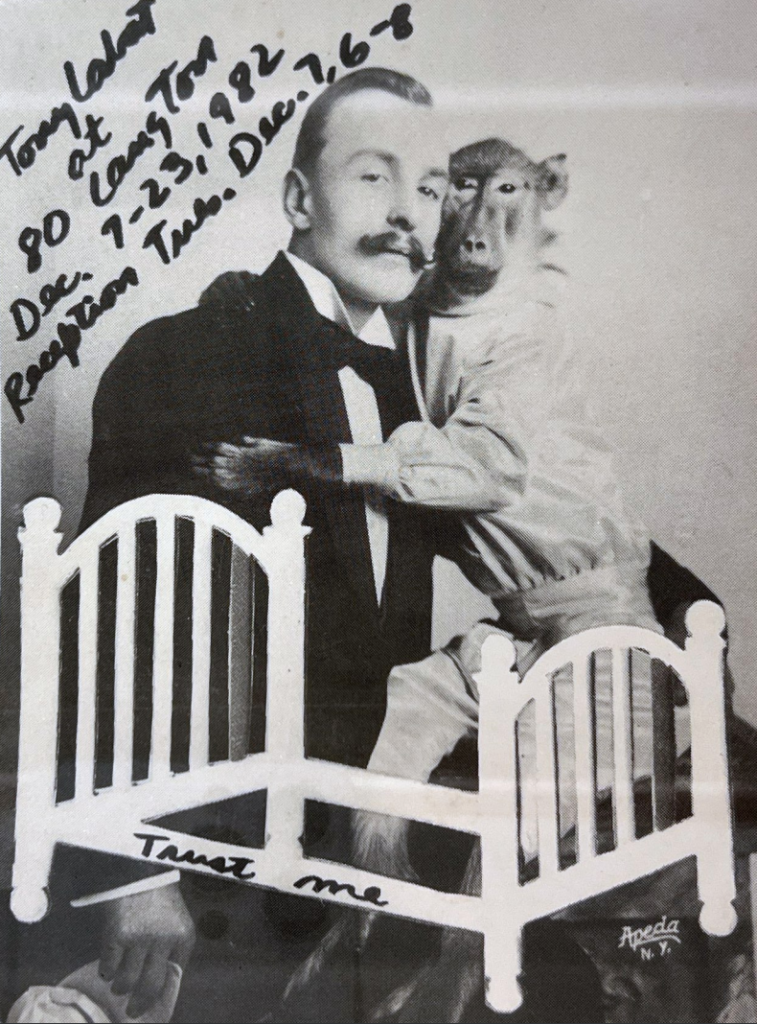

level yet.” [But} I just went in, in a very promotional way, cocky, if you will. I knew when Langton would meet, and I sent them a dozen roses with a bike messenger, with a card that said, “Trust me.”

I had been doing so much performance work at after-hour clubs– they were basically punk galleries that would have bands and sell beer in order to support the gallery. So I had already been doing a lot of stuff in that circuit. I assumed that they heard about me through the noise that I was making. And so I did it. I took my chances. I took my gamble.

So then, to make a long story short, they accepted my gesture. And so I did my installation. It was like getting my foot into this ‘more legit door.’ But I was also very happy with the punk clubs and infiltrating and doing public art – things like that, which I saw more like the real underground, the real alternative to the alternative spaces, in a funny way. Because again, like I said, by 78 [Langton] was becoming very established.

But at the same time, I recognized how it would put my foot in the door, to then apply to the Kitchen, Hall Walls, 911 … and other places like that. So it was a really very healthy support network. And remember, there was also a healthy dose of National Endowment for the Arts grants, which also helped. I never thought that I would end up in a commercial gallery until the mid-80s when it all fell apart.

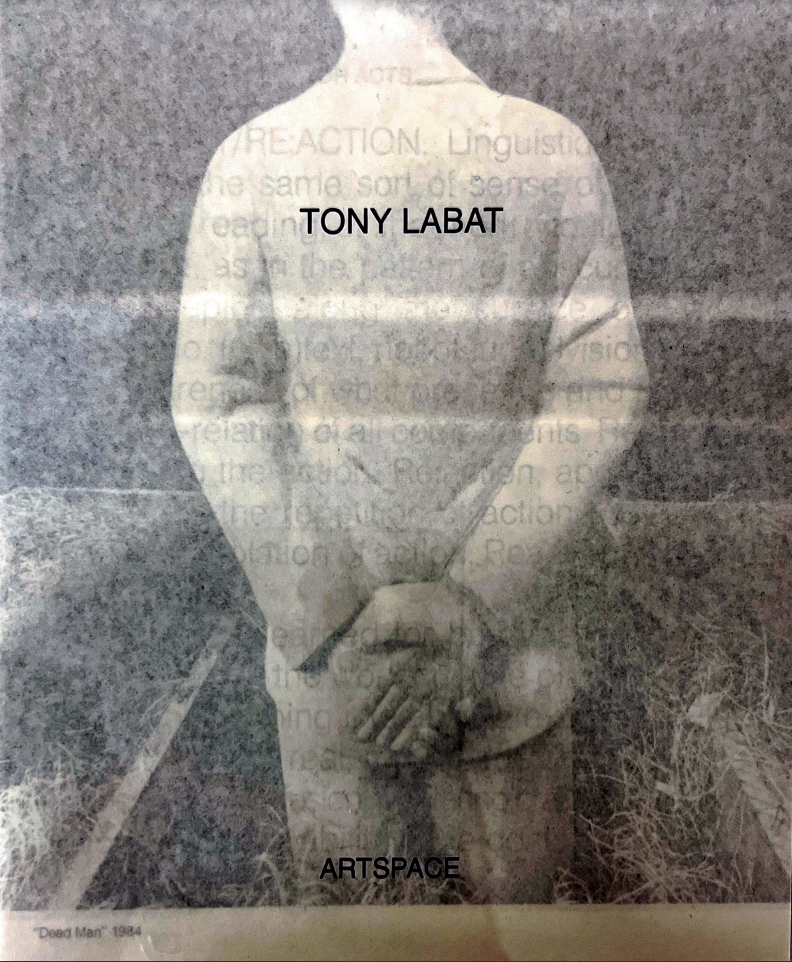

L: As you have previously noted, it seemed that by the mid-1980s, conceptual art was booming in New York, leading many artists to relocate. You moved there briefly, “thinking San Francisco was over,” but soon returned after being offered a teaching artist position at SFAI– which later turned into a tenure of 37 years. Around that time Artspace also opened its doors in San Francisco. When did you become involved with Artspace? How was Artspace different from other alternative art spaces in San Francisco during this time?

T: The New Genres [Department], or PV as we called it, performance video, had a very beautiful dialogue, conversation, connection with CalArts. Tony Oursler was there, Mike Kelly was there, John Baldesari [was] teaching. We had a lot in common in the pedagogy, the philosophy behind it, the kind of work that we were doing.

Karen Finley left. Mike Kelly stayed in LA, but he [also] had gallery representation in New York. Tony Oursler went back to New York. It was happening a lot. I went to New York in 84. And I’m not saying that it was over in San Francisco for conceptual art because there were still incredible, amazing artists from the first generation. But we all know that the thing was painting. Painting came back, the object came back, [and] the commodity and market sort of issues started to come. At the same time, I really was attracted to the Lower East Side and what was happening there… because even Mike Osterhout, [who] was a student with me, left San Francisco to open up his own gallery in the Lower East Side, it was called MO David.

There were all these little holes in the walls– galleries that were really amazing because they were kind of underground, but at the same time selling works and supporting artists. And you have to remember, by then, Reagan cut off the National Endowment for the Arts. There were no more grants, so there was no alternative anymore but to be in a gallery. The gallery scene in San Francisco, to me, was very antiquated and stiff and conservative and regional, so I went to New York to check out the scene that was going on the Lower East Side. I started showing with MO David, Tony Oursler was in the same gallery, [and] Karen Finley. There were a lot of San Francisco artists in the Lower East Side– it was kind of like an exodus, if you will.

In 85, after a year or so, I thought I was there for good. Paul Kos invited me to come and teach and be a visiting artist in the New Genres Department. And of course, that was a dream for me, because [these were] the people, [who] had influenced me. Now I was a colleague, and that was huge. And so I came thinking that it would only be for one semester– talk about life. But then I guess the students talked with Paul, asked him to invite me again and again. And before you knew it, 37 years went by.

Around that time…around 87, I started hearing about this space called Artspace by this amazing woman, Anne McDonald. [She] was on the Board of Trustees of [SF]MoMA…and what I learned about her is that she had picketed outside– literally, with a sign. Imagine a board member picketing outside the museum because it was stiff and they weren’t supporting local artists. [That] is beautiful.

She decided– “look….why am I giving you all my money when I can go and open up my own space and have my own opinion and ambition and ideas of what it should be doing in the community?” –which was amazing. So she opened up Artspace.

She wanted to avoid that kind of policing [censorship] of the kind of exhibitions that she wanted to have or the artists she wanted to support.

[She] elaborated on networks that seemed to have been really lively in the 70s, but [had] kind of dampened with shifting social, political climate.

L: As you noted, Artspace was a multifaceted space, which included Artspace, Artspace Productions and ArtSpace books– including the literary quarterly magazine, Shift. How did Artspace support your work and interest in film and performance?

T: I always loved her “assignments”– I guess you can call them commissions– but I just loved that. A lot of the pieces in the collection have never even been shown because they were just made for her. That allowed me and many other artists to be able to pay rent, to live– because I couldn’t afford living with only teaching one class at the Art Institute, or two in a year.

She [also] gave me a grant for the video production. I was able to make video again, with a budget, [and] with a good production. I was constantly doing contributions for the magazine. I was DJing at the restaurant, and I even did some pieces on the walls – a bunch of artists decorated the walls of the restaurant. It was a real community.

[Artspace] provided so many different platforms for engagement. It wasn’t just Artspace– the space itself. It was the production. It was Shift. It was Limbo. It was all these things that were working in tandem that gave artists opportunities to engage with each other.

L: Tell me a bit about your Artspace Sculpture Grant. What work came out of that grant?

T: In 1987, [Artspace] had an invitational competition.. where a committee [was] set up and they accept[ed] proposals. It was for a Sculpture Grant Award. And again, coincidences of coincidences and ironies– David Ireland was on the board to select the artist, and I got it. I believe that David probably championed my work and myself a lot.

It was an amazing opportunity because [for] the first time I had a very healthy budget to get things fabricated, to work, to do. I had, pretty much, given me what I wanted, when I had said “trust me.” I had free rein to design my show. There was no curator getting in the way or anything like that. It gave me the opportunity to work with real money, with a real budget.

And then I had a taxidermy bull’s head with 100 yards of Blue Velvet. I guess the movie Blue Velvet influenced me, I don’t remember.

Then there was the tank… the silhouette of an [aluminum] tank with a video loop [of] girls dancing on top of the bar. It was [from] a very sleazy [bar] in San Diego. [In the video, a girl] is doing her steps, dancing, and there’s this burly asshole guy reaching out to grab her and touch her and she takes these swift couple of steps back– she doesn’t stop dancing– and she kicks him. And I thought that that was such a beautiful [moment]. I was lucky to grab that scene. That piece was thinking a lot about colonialism and imperialism– just because it looks good, you don’t have the right to invade it. I thought it was a great metaphor for that.

That’s basically the four pieces [in the Sculpture Grant Show].

[I] later I had the opportunity to show all of them in MOCA, in LA. That goes to show the impact Anne McDonald had on my career– that I was all of a sudden showing in museums just by that show, opening up the door for me, giving me that opportunity and trusting me.

L: Going back to your own involvement in the Bay Area art scene– as both an artist, and later, as an educator– what was the symbiosis between SFAI and its New Genre Department and these other experimental alcoves, including Artspace? Did these spaces figure into your pedagogy?

T: She supported the New Genres Department. She would refuse to be on the board of the Art Institute because she was afraid that her money and her support would be used in something else. But she incredibly supported the New Genre’s Department– what we were doing. I remember… I had told her that I wanted to do an assignment with [Fisher] cameras, and without telling me, she showed up in my class. In the middle of my class, she shows up with a camera for every single student.

By then, she had opened another space across from Artspace that she called the Annex– Artspace Annex. At the end of the semester, the students did a show at the Annex. I did about three or four exhibitions with my students [there]. I wanted to get the students away from that “student mentality” and into real experiences. That was the best teaching– to get them out of the classroom and work[ing] towards an exhibition and experience.

L: How did your pedagogy, networks, and community in San Francisco shape your commitment to staying in the Bay Area– despite booming art scenes elsewhere?

T: The students. Yeah, the students. It gave me so much that I couldn’t give it my back. I would have that question a lot like, why are you still here? Why are you still teaching? And I think it was the students, my colleagues, we had a really tight [community], when it peaked in the 80s and 90s, [it] was Paul Kos, Howard Fried, Doug Hall, Sharon Grace. What more can you ask for? I could see the faculty in the other departments bickering, and it was just not that scene for us– we respected our differences.

Faculty didn’t want to touch performance art because it got to be a dangerous, liability driven issue. And I was constantly, I say with humor, in the Dean’s Office, every semester, because of a performance that was happening in my class or a performance that happened on the rooftop– and I got so tired of it [but] I was the only one committed to it because it was an important form to know. I was pretty much alone with taking care of performance and video in particular.

One thing that I loved about my job was the international level of the students– I love that diversity that we had. I could have [students] from Iceland to Iran to Mexico, Brazil. You name it. So it was forcing us to, or at least I would try to patch it in, [to] recognize the difference in aesthetics– cultural aesthetics and everything else.

Personally speaking, I [also] have a daughter, and I think that was another reason, very huge reason– I wanted to be there for her. I was a single parent. I raised her by myself. The combination [of] my daughter, [and] me trying to keep the torch going at the Art Institute, the pedagogy that I call my teaching–it was a form of activism for me.

In 1999, I met Los Carpinteros, the Cuban collective. I met them in New York through Carlo McCormick, the critic. They opened up my eyes to so many things that were going on at this school, [at their] art school called ISA [Instituto de Arte Superior] in Havana. Rene Francisco was teaching there, and his pedagogy and philosophy was exactly like what I was doing. It was amazing. And I could see that with their limitations, they were doing videos and installations and performances.

I went into the Dean’s office and I told him, “I’m going to take a class to Cuba,” and he approved it. We went through Tijuana, not knowing what to expect. And that was the beginning– it changed my life forever.

I wanted to bring the students and meet with the Cuban students of art [and] artists, and do studio visits. In a way, I [was also] surrounding myself with my students, almost like a protective device, because it was very emotional for me. I hadn’t been back since I was 17 years old, since 1980 [when] the Soviets were there. I didn’t even recognize the island. I didn’t recognize my people. So going back, little by little, I started meeting the artists there, and I started going. I kept taking students for about 15 years to Cuba every year.

It was a real bridge, people to people, culturally– and at the same time was hard because I had to spend time with the students about how to look, about engaging with the taxi driver, about politics, [about] the macho culture that still existed, all of that. I had to warn them– the billboards, the propaganda– to understand the culture, and that we were only here to learn. We were not here to critique.

I think for the most part, 99% of my trips, it was the best teaching I’ve ever done because it wasn’t just art, it was life…

At the same time, in 99, I became Chair of the New Genres Department. That allowed me to go “okay, finally I can do with this program whatever I want to do, what I’ve been wanting to do for a long time.” So I started bringing guests. It gave me an opportunity to bring [a] younger generation of artists to teach and give them an opportunity– it was incredible.

I had Los Carpinteros cooking in Pete’s Cafe at the Art Institute. I brought Tania Bruguera to the gallery. Rene Francisco, the professor at ISA– we gave him an honorary doctorate degree… I kept bringing them, Raul Cordero. You and I know that during those days, in the early 2000s, Cuban artists were hot. The market was there. I saw bus loads of curators and dealers and collectors in Havana going to all the artist studios. So I knew what was going on and I wanted to expose that to the students and the Art Institute. Even Ella [King Torrey], rest in peace, the President [of SFAI] went on one of the trips with me. And she brought a bunch of the Board of Trustees with her.

After that, I became Director of the MFA program. I was the director of all the programs: photography, sculpture, painting, printmaking, filmmaking, ceramics, etc. Now I [could] influence the whole. I had a target on my back from a lot of the other faculty. But I loved it. I really loved it. So I think that really also was instrumental in keeping me there. I just felt like there was a reason for me to be there and I was contributing and I should be there.

This interview originally took place on September 13, 2023