There is a Terrible Heaviness of Life in all Things Animate and Inanimate

“Delving means touching too deeply. Pressing your hand instead of using that lovely light flickering touch you just showed me. It sometimes happens unintentionally, when dream-givers become too interested in what they are touching. When they start to like it too much.”

-Lois Lowry, Gossamer, 20061

There is a terrible heaviness of life in all things animate and inanimate. The inanimate are voyeurs of the animate, catalysts for memory and imagination, and triggers for the conscious beings who collide with them.

The house is one of these vessels for memory and time, encouraging a delving into yourself that pulls your imagination to the surface. You can allow your touch to be “light and flickering” or you can be a “pressing of your hand.”2 Inside of every home, in whatever form of shelter, lives the essence of the person that inhabits it.

Our first home is the beginning of our collection of images as memories. Everyone inclines to specific parts of a house reminiscent of their childhood home. Perhaps there was a particular window of a bedroom that collected condensation at the edges and dampened the sill, a translucent portal that transformed your blank reflection of the night into the collection of tangled branches on the backyard tree by the morning. Or maybe you had a wall that curved in a peculiar way, the feel of its cold skin under your fingertips and the habit you had of dragging your hand over it as you passed. This delicate gesture made it seem as though it was rising to your touch like a timid animal.

This collection of memories entwined with inanimate objects and space is interpreted as “values of inhabited space,” by Gaston Bachelard. It describes the way memories give value to inanimate objects within occupied space. In his book Poetics of Space, Bachelard describes his musing and theories on the “values of inhabited space” within the home. According to him, the house is full of memories. These memories fit in certain intimate spaces, as big as the attic and basement, or as small as inside of cupboards or wardrobes. The difference in size relates to the scale of intimacy created within them. As naturally sentimental and intimate beings, we discover in our first homes how inhabiting these semi-private spaces allow for comfort and creation of self.

This concept is most commonly tackled in literature because, I believe, we are conditioned to think in words instead of pictures and feelings. More likely, we are conditioned to translate our thoughts from feeling and images into words automatically. But all memories are wells of feeling we find ourselves falling into. We are pushed into the vast depths by an image confronting us, sometimes brutally taking away our breath and enfolding our minds, and sometimes as gently as a caress. At times it is a light touch, and at others it is a pressing of a hand. This idea of memories triggered by specific interactions in space can also present itself in visual art. In image-based art, pictures can be talked about as languages, similar to symbols but more universal. Different pictorial descriptions and materials trigger different memories as states of feeling for the viewer. Sometimes the feelings are so vivid they spark a specific memory. Sometimes they produce just a tickle of remembrance, the way Andrew Wyeth’s paintings reminds me of the feeling I get at my grandma’s farm. This triggering of memories through interaction with specific pictures in visual art becomes a language of memories. David Ireland used this language of memories to enfold the viewer in an intimate reverie.

In using recognizable materials in his sculptures in concrete, wire, wax, and household objects, he has created a dictionary of this memory language that delves the viewer into remembrances so light that they barely tickle the fronts of the viewer’s mind. Instead, these feelings sit within them as small breaths of air, familiar enough to create a comfortable state of awareness. (Ireland) “favored working with these ordinary materials because they were inexpensive and universal and most important, because their character was homely and artless”3 described by Karen Tsujimoto in the catalog accompanying his 2003 retrospective exhibition “The Way Things Are.” Ireland’s use of these familiar materials creates an almost immediate intimacy with the viewer. As a result, these objects demand value within any space they occupy. Though they are too vague to trigger specific memories, the use of these images activate states of feeling that send the viewer into a complex network of their own memory language.

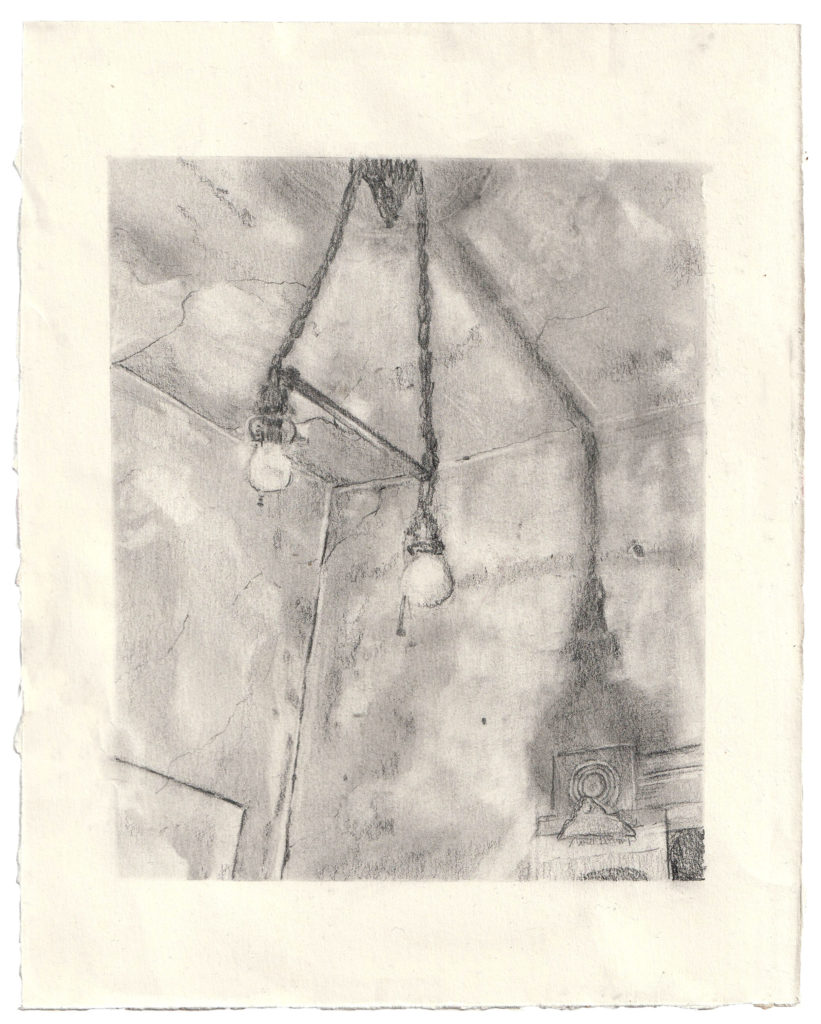

One of Ireland’s most important and influential works was his San Francisco Mission District home at 500 Capp Street. It is his studio, gallery, and home, filled with his sculptures and paintings, and in-and-of-itself a sculptural and performative living artwork.

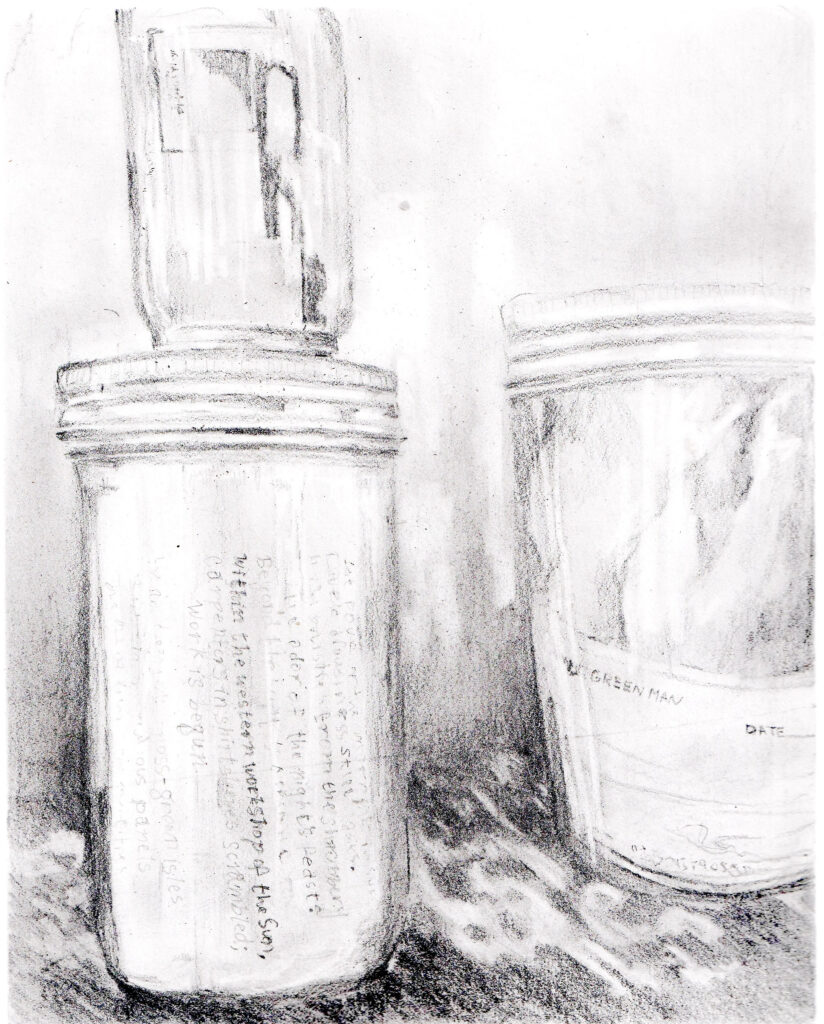

“All really inhabited space bears and the essence and notion of home… an entire part comes to dwell in a new home… In this remote region (the house) memory and imagination remain associated, each one working for their mutual deepening,”4 writes Bachelard. He goes on to say, “Space contains compressed time, that is what space is for.”5 So what if someone were to compress the space even further? Force the time within the space, the memories and experiences, together in a small container requiring them to touch one another, to rub against each other and causing them to engage in consistent dialogue? Ireland was a collector of intimacy. Within his large Victorian home sits hundreds of glass jars, filled with memories democratized by these glass enclosures ranging from remnants of birthdays past to dust from his front stoop. To Ireland, it seems every moment was worth experiencing. He put his experiences into jars and put the jars into cabinets. With these jars, he achieves the ability of inhabiting a space while working with imagination and memory to create a feeling that intimately touches the visitor. When we live in a house, we leave marks of our physical existence on the walls and floors, and the essence of ourselves in the space inbetween. Similar to a luminous slimy trail of a slug or snail these experiences and feelings that, though they fade over time, will always exist within the space, and for Ireland he placed the artifacts from these experiences into jars.

These jars are sequences of memories preserved in glass, like jams or pickles. The glass capsules allow the visitor to consume it’s contents without having to break the seal, though leaving much to speculation for few of them are labeled, and the cylindrical shape leaves the core concealed. None of the jars have ever been opened. If one were to break the seal, would the memory slide out, tentatively touching the things around it unsure where to go after decades of being shut in and marinating in its intimacy? Would it be a Pandora’s box of emotions and memory exuding out of the freshly broken seal that our sentimental minds would engorge with delight, or would it simply whisper past us barely brushing our ears as it disperses into the nothingness of air? Maybe it would simply just join the essence of aliveness in the house transforming into a new way of being.

The David Ireland House at 500 Capp Street is a preserved collection and reflects Ireland’s way of inhabiting space. It is the snail’s trail delicately contained within a glass jar, but not just a preservation of the way he lived for the benefit of future generations, the house is a jar itself.

- Lois Lowry, Gossamer (New York, NY: Randomhouse, 2006). 24 [↩]

- Lois Lowry, Gossamer (New York, NY: Randomhouse, 2006). 24 [↩]

- Karen Tsujimoto and Jennifer R. Gross, The Way Things Are: the Art of David Ireland (Berkley: University of California Press, 2003), 11. [↩]

- Gaston Bachelard, Poetics of Space (Boston: Beacon Press, 1994), 27. [↩]

- Gaston Bachelard, Poetics of Space, 30. [↩]

Bells Howard (They/Them) is from Portland Oregon and currently resides in Oakland, California. They are currently pursuing a BFA in painting from the California College of the Arts and have taken classes at the San Francisco Art Institute. Howard is an Artist Guide at The David Ireland House.