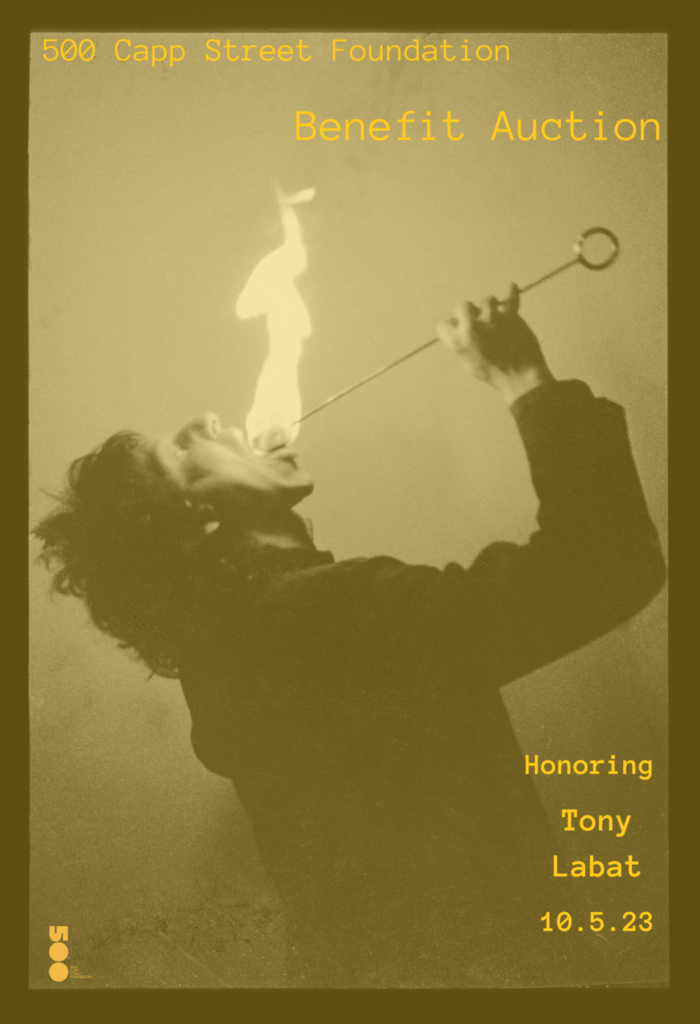

Join us in honoring Tony Labat at Capp Street’s Benefit Art Auction on October 5th.

Tony Labat is a second generation, pioneering video, performance, and conceptual artist. Throughout his 37-year teaching career at SFAI, he fostered experimentation and risk-taking to which his impressive roster of artists/students attests. He and David Ireland shared a long and meaningful relationship, having each come to their art practice at SFAI later in life. As a testament to their life long friendship and mentorship at 500 Capp Street, we are thrilled to honor Tony and his life’s work at this year’s benefit art auction. As Tony recalls, “The house involved the body, labor, site specific work, context, performance, and art/life issues. It was a huge part of my influence and education and opened up all possibilities of what art could be.”

Full interview here: Tony Labat interviewed by Jennifer Rissler.

J: You are a Cuban refugee and arrived in Miami in 1966 on a Lyndon B. Johnson Freedom Flight. Can you talk a little bit about how you found your way to San Francisco in 1976?

T: After having owned a platform shoe store in Miami, and gone through a divorce, I had had enough. I was questioning a lot of things. So I enrolled in Miami Dade College night classes. I was lucky to have two really amazing teachers – one instructor, Robert Thiele, told me I should not be there, that I should take real classes, which I did. I quit my job and dedicated myself to that. Robert started paying attention to me, I was experimenting with ideas that were intuitive, using cameras to document myself. He brought me exhibition catalogs and magazines to peruse; I was seeing documentation of performances in New York City and San Francisco, and getting familiar with the work of artists such as Les Levine and Chris Burden that Robert introduced me to. Robert was in the Whitney Biennial 1975: Contemporary American Art. He was a contemporary of Howard Fried, and he came back from the biennial and told me that Howard was purchasing portapacks and attempting to start a Performance/Video department at SFAI. Not even thinking about it, I sent away for a catalog, put slides together, sent them off and they accepted me. I never visited the campus…I got into my Volkswagen bus and drove to San Francisco…and the rest is history. I went there to meet Howard Fried. I had a very specific agenda.

J: What role did Bay Area artist-run spaces play in your trajectory as an artist?

T: HUGE, especially in 1978. I sent a dozen roses to Langton, with a card that said “Trust Me” – I sent them with a bike messenger to be delivered during a meeting of the artist/proposal review committee. Alternative spaces were becoming established, they were getting grants, their ethos had a lot to do about letting an artist fail/experiment on their own. So essentially, I sent a jab about that- to trust me – if you want experimental work we have to be able to experiment. At that time I was an undergraduate at SFAI. Alternative spaces like Langton were huge for me, and opened doors. I owed a lot to Renny Pritikin and Jock Reynolds, who founded the space. Langton had four wooden columns in the middle of the space and it was a difficult space but I was working with site specificity. I made a ring, like a boxing ring. I stretched wire 5” from the floor – ankle length – and all lights were out, the space was completely dark with the exception of one red square spotlight in the middle of the ring. I was thinking about how insects get drawn to light. In this context, people would trip on their way to the light. Often I’m asked if I would recreate this type of work now. No one would touch it today because of liability. I was thinking about addressing the body, paying attention as a way of setting up a trap for your own presence, feeling your own body in space.

J: In hindsight, how did attending SFAI and teaching at SFAI affect your trajectory as an artist?

T: After going to SFAI and meeting Howard Fried, in 1978 a lot of things started happening for me. Helene Fried, the Director of SFAI’s Walter & McBean galleries was very instrumental in my trajectory. A few key things that I recall are meeting Tom Marioni at MOCA, the Museum of Conceptual Art. He was looking for a janitor and I became his protege so to speak. I met Tom at MOCA and he would give me incredibly beautiful daily tasks. MOCA was an old, battered warehouse. For example, he would ask me to go to a grimy sink and clean it – but the sink didn’t work. I would spend all day cleaning a sink – like a sculpture. Another time, there was a leak on the above floor, and I did a series of canals that would throw water out the window. On Wednesdays, I would go downstairs to Breen’s bar, drinking beer with friends – David Ireland and Paul Kos were regular attendees. I was still an undergraduate at that point! Helene mentioned to me that an artist named David Ireland was working on a project, at 500 Capp Street. He wanted someone to document his process. I was already documenting myself in studio 9 at SFAI, so I was interested in documenting performance. So really, the trinity of working in studio 9, going to MOCA several times a week, and going to 500 Capp Street almost every day to document David’s work was my foundation. In Miami I was shown Picasso and the history of painting – it was as if history stopped with Warhol! Getting to San Francisco was an eye opener for me. I fell in love with conceptual art and idea-oriented work, applying materials and form to the idea. It was eclectic, all over the place, but I often would think – some things need to be screamed. You get influenced by something or inspiration from it- is this a video, a ready-made, an object, a sculpture? That is how my process worked for me. I was influenced by the political, the cultural, popular culture, media, etc. I was very influenced by all of it.

I started showing my work in video festivals in Europe, and at that time San Francisco had its own video festival that was very international, between 1982-1987. In Southern California, the Long Beach Museum of Art had a television studio, and I was invited there based on a proposal I submitted to work there. Around that time, I met Tony Oursler and we talked about generations – we were the second generation of video artists and we grew up with TV. We were making television. The shift from grainy black and white portapack to editing and color and professional editing was a huge influence on us. With editing you think about the composition of the frame, sequencing, and engage in a lot of storyboarding and planning the script. Between 1978-87 I was very active with video. BAVC (Bay Area Video Coalition) was a very important space, and they gave artists discounts for editing. I started getting grants from the NEA. SFAI provided access and exposure to artists. Through Howard, I met Linda Montano, Barbara Smith, Vito Acconci, and Chris Burden. There was LACE in Los Angeles, The Kitchen in New York City. These alternative spaces launched my career.

By 1984, the general thinking among San Francisco conceptual artists was that we had to go to New York City. I moved there thinking San Francisco was over – I was there for a year, and in 1985 Paul Kos invited me to teach in SFAI’s New Genres department, the former Performance/Video department. It was a huge honor to be a colleague and to go from student to colleague. I was supposed to be a visiting artist for a semester, but the students responded to my teaching and asked Paul to retain me. Little by little I ended up there for 37 years! I wasn’t a teacher; I saw myself as an artist in a lab experimenting with students. I got tired of going to the Dean’s office because of student performances! SFAI advertised that their pedagogy was experimental but when we would experiment I was the one in trouble. And then the 1990s came and I had to adapt to the circumstances and limitations of that decade. Teaching became an extension of my work. It was a two-way street: what the students were giving me and vice versa. With the rise of multiculturalism and political correctness, you had to watch out for what you would say, especially in the context of identity politics. It was a constant cultural thermometer to be in the New Genres department at SFAI. It was confessional, autobiographical, and emotionally naked. What Howard Fried created was not about conventional teaching models and all I tried to do was to fill his big shoes! I refused to become a “teacher” – I hated the term “professor” – I was an artist sharing his experiences with students.

J: When did you first meet David Ireland? How did your relationship evolve over time?

T: In 1977. It started with me going to 500 Capp Street, which was his studio and his home. We immediately hit it off, and the chemistry was there. He would just describe to me what he would do daily, like sanding floors, varnishing, taking off wallpaper, etc. He was doing his actions – his maintenance activity as he called it – and I was trying to set up shots and follow him. There was no conversation and he never would acknowledge the camera. We both were doing our tasks at hand. We would have breakfast or lunch at Jim’s restaurant on Mission Street to take a break and have conversations. We talked about art, it was so philosophical, we really hit it off and we shared a sense of humor too. He appreciated my prurient sense of humor! I also think that, because I had owned a business, had been through life, and I was 25 when I got to SFAI and because he had a life too – his safari work in particular – we both came to art later in life. We shared that in common. We also shared the romanticism of Ernest Hemingway, with his big game hunting and the fact that he had a home in Havana. David would give me Hemingway books. Overall, we had an incredibly close friendship. There was nothing as special as going to 500 Capp Street – to have drinks by the fireplace or to cook together and have dinner. We kept growing and developing and we became very close. I didn’t see him as much when his work took off, but after he broke his back in Idaho we got back in touch. I was the last one to see him alive – shortly before he passed his nurse called me because she knew how close we were. I was there in the evening, and 2-3 hours later he passed. I just held his hand – he knew I was there at the end.

J: How do you see 500 Capp Street evolving in light of SFAI’s closure? What does 500 Capp Street mean to you?

T: At first, after David passed away, there were opportunities to talk about the future of the house. It was still very fresh and difficult for me, and I almost felt like I saw it as not right – but after the house was purchased I looked at it differently – not as a piece of real estate. I started shifting but it was very emotional for me and hard to see his things. Ultimately, I saw the potential for what it could be and the legacy of what it represented. The house involved the body, labor, site specific work, context, performance, and art/life issues. It was a huge part of my influence and education and opened up all possibilities of what art could be. It was iterative, moving through stages and I am glad it went through a rough time, because it came out amazing and beautiful. I am proud to see myself as part of it – the legacy. Now new generations are getting to know its legacy and history, and that is beautiful.

J: What advice would you give to emerging, conceptual artists in San Francisco?

T: I think it has a lot to do with the decades and movements and how things shift. A lot of New Genres was based on that philosophy – we didn’t deal with craft like other departments; rather we were constantly paying attention to the political, cultural, and personal shifts at play. Work that influenced me was very personal and bordering on autobiographical. When the NEA stopped giving grants to individual artists we encountered yet another shift. In the 1980s, I started showing with galleries, eventually ending with Paule Anglim. I was not yet comfortable with a store-like setting that a gallery represented and how success was measured by how much you sold. I had been more in a world of grants and alternative spaces, shifting my conceptualism to sculpture, to object making, projects or installations. There was nothing to sell! Then the politics of the 1990s came into play with multiculturalism, and then the 2000s with identity politics and activism. I don’t know how I’d define conceptual art in San Francisco or if it’s even there. There is a legacy of working with ideas and applying forms and tools to the idea, and I would suggest or promote that process, whether activism, protest art, political work, work that deals with immigration, climate change, etc. You can jump to different materials depending on your ideas.

I talked to Tony Oursler recently about the difficulty he is having in New York City with video, as everyone seems to want painting! You have to be in tune with shifts and what is happening in your particular community – what is happening in San Francisco is not what is happening in New York or Los Angeles. San Francisco may not be the best place for a conceptualist – who knows? Learning how to see what we look at – for inspiration – even watching media can be important – you must be aware of what is going on in the whole landscape. Place – my environment – influences me – whether architecture, weather, the political climate, etc. Respond to your environment – make it personal – that is what David did! The hybridity of his actions, which aesthetically involved craft and labor, combined with his ideas, his philosophical approach – using labor and duration and process – he managed to put all the thoughts that were in the air into one container. There is a hybrid studio and post-studio philosophy about the house. Which is his lasting legacy.