The Earth Touching Buddha: The Moment of Enlightenment for David Ireland

“If I had a prior vision, in Burma it all became a reality, and for me this trip really started there…There is some magic here and it can only be explained by some history of Devotion.”1 This is an excerpt from a letter David Ireland wrote to a friend while on his trip to South and Southeast Asia in 1975. In another letter to his mother during the same trip he wrote, “I suppose that I should not be so pleased to see this kind of thing and I confess that what appealed is the primitive state of things.”2 These two statements together define the complexity of colonialism and the tangled web of perceptions that has lingered in contemporary Western societies. On the one side, Western cultures often admire, and even yearn for, what appears to be the simplicity of “primitive,” or non-modernized cultures. On the other side, some, but not all, recognize that they are contributing to the overall perception that these cultures are only valuable as long as they remain in a stagnated, pre-industrial state. Through research, one can gain not only appreciation for other cultures and their expansive histories, but also learn ways to respect them without projecting onto them Western colonialist ideals. David Ireland’s letters not only serve as a window into his mind to let us know how he thought about the world around him, but they also serve as a gateway to understanding why he kept certain objects in his home.

During Sherwin Rio’s exhibition, As Above So Below at 500 Capp Street in 2022-23, he took various objects from Ireland’s collection and placed them on a table in the Paule Anglim Archive Room in the basement of the house. These objects had previously been located throughout the rest of the house, many of them in the dining room. By moving them to the basement, Rio encourages contemplation of the interdependence that exists between the house and these foreign, often exoticized, objects. On an even deeper level, Rio stimulates conversations regarding American society and the colonialist foundation on which it was formed.

At first, the origins of many of the objects were still unknown, and the Organization, in light of their desire to decolonize the archive, began conducting provenance research. Among these objects was a seated wooden Buddha statue, which appeared to be of Southeast Asian origin. This statue, seated in a double lotus position3, although difficult to make out now because of its broken off right arm, is in the Bhumisparsha Mudra position, or the Earth Touching Buddha.4 The Bhumisparsha Mudra position is defined by the Buddha’s left hand resting gently in his lap with the palm facing up, and his right hand resting on the front of his right knee, palm facing inward and fingers extended and touching the ground.5 The Buddha, who had reached enlightenment under the Bodhi tree and gone up to heaven to teach celestial beings, then returned back to earth to continue his mission of teaching earthly beings about Buddhism. The Bhumisparsha Mudra is significant because it is a reminder of the moment when the Buddha “returned to his physical body under the Bhodi tree and touched the earth, thus the very act of realizing enlightenment as the historical Buddha Shakyamuni.”6 Initially, Indian Bhumisparsha Mudra Buddha statues were accompanied by other storytelling symbols such as, a small Bohdi tree above his head and a flame that is attached to his ushnisha. The ushnisha is a round lump on top of the Buddha’s head under his hair.7It is often called the Buddha’s “second brain” because he acquired it at the moment of enlightenment. As Buddhism traveled into Southeast Asia and the story of his enlightenment became more popular, the additional storytelling features disappeared, and a more stylized version of the Buddha emerged.

The seated Buddha statue from Ireland’s collection appears to be an example of statues from Thailand and Myanmar (Burma). In these regions, Theravada Buddhism, or the way of the elders, was most prominent, and is reflected in the way their statues were made. Theravada Buddhism emphasizes the Buddha Shakyamuni by highlighting early relic traditions.8 In other words, these statues focus on the Buddha’s body by minimizing external factors such as, acknowledging the presence of his garments through minimalistic outlining, and defining the “Earth Touching” moment through only the downward extension of the right hand’s fingers. After a considerable amount of research, it was inconclusive as to whether Ireland’s Buddha statue came from Thailand or Myanmar, considering many features were similar to statues from both countries. For example, in Thailand the head is elongated, the fingers are all equal in length, and the body appears more “fluid.”9 All these characteristics apply to Ireland’s statue. However, similarities between Ireland’s statue and Buddha statues from Myanmar also surfaced after extensive observation of statues from this region. For example, Myanmar Buddha statues are often seated in a double lotus position, whereas in Thailand they are usually seated in a single lotus position.10 Additionally, Myanmar statues appear to be seated in a declining angle with their hips higher than their knees. On the contrary, Thai statues appear to normally have their hips and knees at a parallel height. Furthermore, the most common material in Thailand is bronze, but in Myanmar the preferred material is wood.11 Finally, Ireland’s Buddha has been painted with what appears to be a red lacquer, which was determined after close observation of a Buddha statue from Myanmar on display at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco.12

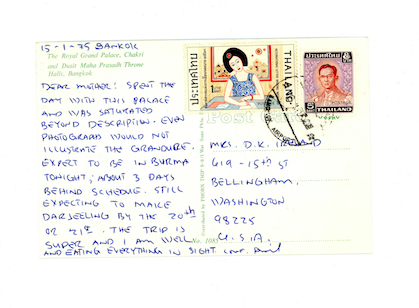

Researching the provenance of Ireland’s Buddha statue was the first step in formulating the reason as to why this object came into his collection and what special significance it held for him. The second step was looking through the archive and reading his letters and postcards to friends and family back home. Although a definite point of origin cannot be determined at this time, I am left wondering if this statue is from Myanmar, and possibly, from around the location of the ancient kingdom of Bagan. In the letter to his mother, Ireland wrote that he “spent 2 days there crawling through temples and climbing to the tops of some to look out over the Irrawaddy.”13 On this trip in 1975 Ireland visited India, Singapore, Thailand, Myanmar (Burma), and Afghanistan, yet it is only Myanmar that he writes about extensively in the letters to his mother and friend.14 It is evident through these correspondence, that even though Ireland traveled multiple times to Thailand and only once to Myanmar, it was ultimately Myanmar that captivated his heart.15

The provenance research conducted was inconclusive in determining how Ireland acquired this statue, making it impossible to determine whether he obtained the sculpture by legal means. This alone raises many questions concerning decolonization and repatriation of objects, which will continue to be discussed throughout the upcoming decades in Western society. However, I would like to highlight an interesting observation between David Ireland and the Buddha statue in his collection; although, I cannot say whether Ireland himself realized this connection. The Buddha statue Ireland brought home is a representation of the exact moment when the Buddha returned to earth after he had achieved enlightenment. It is possible that this statue in a parallel narrative could represent the moment that Ireland returned from his spiritual journey in Southeast Asia, where he also had achieved a level of enlightenment. Nearing the end of his journey, Ireland acknowledged both his admiration for the country of Myanmar and its people, as well as his Western exoticized biases of their “primitive” state. In the latter part of his life Ireland demonstrates his desire to continue incorporating Buddhism, and specifically Zen Buddhism, into his daily life.

In conclusion, this provenance research has not only opened doors to Ireland’s past, but it has also conveyed that his perspective gradually changed throughout his life. This notion of continual change, or impermanence, is a core Buddhist concept; and Ireland, who previously made a living by selling “exotic,” and somewhat controversial, objects from Africa, demonstrated his ability to recognize colonialist thought patterns. I cannot speculate whether Ireland would have articulated that this perspective was colonialist, which has now been defined as being systemically embedded in Western culture and society. Nonetheless, we can use his “moment of revelation” as a stepping stone to decolonize 500 Capp Street’s archive, and in conjunction critically address notions of colonization with American history.

- David Ireland, “To Love,” January 25, 1975, Paule Anglim Archive. [↩]

- David Ireland, “To Mother,” January 1, 1975, Paule Anglim Archive. [↩]

- Double lotus means that the figure is seated with both legs crossed in front and both feet are stacked on top of the opposing knee. [↩]

- Kurt Behrendt, How to Read Buddhist Art (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2019), 72. [↩]

- Louis Frederic, Buddhism, Flammarion Iconographic Guides, trans. Nissim Marshall, 1st ed. (Paris: Flammarion, 1995), 44. [↩]

- Behrendt, How to Read Buddhist Art, 69. [↩]

- Samantha Thompson, “Buddhist Statues, Inside and Out,” Penn Museum (blog), August 29, 2018, https://www.penn.museum/blog/museum/buddhist-statues-inside-and-out/#:~:text=An%20ushnisha%20is%20the%203,or%20Sakyamuni%2C%20the%20historical%20Buddh [↩]

- Behrendt, How to Read Buddhist Art, 72. [↩]

- Frederic, Buddhism,26-27. [↩]

- A single lotus position is when the statue is seated with the legs crossed but only one foot is resting on top of the opposing knee. I came to this conclusion after extensive observation of Buddha statues within the online collections of the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, among a few other online sources. [↩]

- Frederic, Buddhism 26-27. [↩]

- This was determined after comparing what appears to look like red “paint” on this sculpture to remnants of lacquer on the Standing Crowned and Bejeweled Buddha from Myanmar (Burma) at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco in the Southeast Asian Collection. [↩]

- Ireland, “To Mother,” January 1, 1975.Longer excerpt: “After Mandalay I went to Pagan which was the old capitol city of Burma and dates back to about 150 A.D. There is the remains there of an estimated 5000 pagodas and I can almost attest to that fact. I spent 2 days there crawling through temples and climbing to the tops of some to look out over the Irrawaddy.” [↩]

- Alex, “Travel Confirmation” (Travel Spectrum, November 27, 1974), Paule Anglim Archive. [↩]

- Karen Tsujimoto and Jennifer R. Gross, “Chronology,” in The Art of David Ireland: The Way Things Are (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003), 191–97. [↩]

Kelly Velasco is a recent graduate from the University of San Francisco (USF) with a Bachelor of Arts in Art History and Museum Studies and a Minor in Chinese Studies.